With the Quality of Advice Review potentially shaking up several elements of the advice process, we are provided with yet another risk for advice practices to stagnate on their journey of continuous improvement.

It’s a story we’ve seen a lot of over the last ten years. There’s regulatory change coming, so let’s halt all decision-making. Whilst this is occasionally warranted usually it’s not. For most advice practices (and certainly most of the ones who would take an interest in our writings), the absolute minimum legislative bar is not where they have their sights set in general.

In practice, a sweeping statement of “It’s all going to change soon anyways” is not a harmless oversimplification. It’s plainly incorrect. Even if aspects of the advice documentation process do change, many things won’t. In particular:

- What your clients expect to receive in writing won’t change;

- What is important enough for you to want to communicate it to your clients in writing won’t change;

- What you’ll want to communicate to your clients in order to defend against a complaint won’t change;

- The benefits of a final, complete, and comprehensive single document and associated client sign-off won’t change.

With these in mind, focusing on minimum ‘Statement of Advice’ requirements is a complete distraction from what is important. The question we should be continuously reflecting on is: What do we want our final advice document to say?

Get that right, and actual Compliance requirements are administrative in nature.

A rose by any other name

Regardless of what it might be called, what might come after, or what might follow, we’re likely to continue using a single definitive advice document for some time.

That’s not because ASIC said we must, but because there aren’t a lot of better options.

It’s hard, I mean really hard, to separate out why everyone hates SoAs from SoAs themselves. However, consider that:

- Just because something is misused doesn’t mean it’s bad; and

- If requirements must be met, they must be met somewhere, and wherever those requirements are met would still be audited and subject to action or complaint.

Taking a contrarian view, let’s stop and think about what you as a modern professional adviser would want to put in a single definitive advice document, even if someone wasn’t telling you that you had to.

What your clients expect to receive in writing

You’d probably want to back up what you said with, you know, numbers.

Let’s back this up with a common innovation technique, looking at analogous situations that don’t have quite the same variables, in this case, our regulatory requirements.

- A simpler time: If we look back to a less onerous regime from our past, a Customer Advice Record may have been enough to satisfy most client expectations in 2000. However, that’s long gone now. Back then Google wasn’t a verb, in fact, AltaVista was more popular. Clients are now far more informed.

- Similar professions: Looking across disciplines, lawyers and accountants may not have to issue nearly as much in writing as we do, however they do produce something in black and white. Stockbrokers will vary, however when constructing a portfolio it’s not uncommon to see a written report that exceeds their minimum requirements and better reflects the fee which they charge.

I’d say similar professions would be a better indicator for better advice practice, rather than harking back to a time long gone.

In some respects, advice fees have become a vicious cycle now. Costs to produce advice go up, so clients have to pay more, clients are paying more so their expectations go up, increasing the cost of production, and so on. If you paid $550 and got a Customer Advice Record, that’d make sense. Pay over $4,000 and expectations go up. This isn’t a case for padding out a document, far from it, but there’s a minimum expectation that exists all the same.

What is important enough for you to want to communicate it to your clients in writing

Whilst clients may be aware of the broad strokes you have in mind, advice is complicated. You can’t practically gauge every client’s reaction to every possible downside throughout the advice process. Without a sufficiently detailed written document, you can’t practically communicate everything. Whilst a document may well be complemented by video, this is a significant impediment to removing the single definitive written document from the advice process.

There are also those items that are important enough that you would labour them no matter the format and even if you could guarantee a client wouldn’t complain.

Verbally, in video, or in writing you may well want to make the impact of your advice very clear to a client. This is especially relevant where there are very real trade-offs, irreversible decisions, or major risks if a client acts independently. This isn’t compliance management, this is good client education and good planning.

What you’ll want to communicate to your clients to defend against a complaint

Regardless of what happens, there will be aspects of an advice document that you’ll want to have disclosed. It’s an unfortunate reality, but disclosure does have some value when it’s not overused and not relied upon too heavily.

Whilst this has a lot of overlap with the above, it’s looking at it from a different perspective. This isn’t about what the client should be aware of, this is what you might need to defend against. This can be a trap, where every fathomable downside can be included without the discipline to weigh up if this is indeed important enough to include. This can vary depending on the risk appetite of the business. More on this below.

The benefits of a final, complete, and comprehensive single document and associated client sign-off won’t change

Regardless of what may come through the Quality of Advice Review, use of multimedia, or otherwise, there will always be significant benefits in a single document that covers everything at that point in time and has a linked authorisation for signature. Whilst the name, mode, length, style, and more may change those benefits shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand.

As a powerful risk management tool, this is likely to be required by licensees and Professional Indemnity insurers for some time to come.

When looking at the above benefits of a single definitive advice document, without even considering any uncertainty over what might happen with regulation, we may actually want one. Especially if we can avoid the mistakes of the past and present.

So, if we can consider that there could be merit in one, we can look at how to do it right.

Start with the customer experience

This is where the conversation is most important. This is where it should have been when practices or licensees consider investing in their advice documentation, and this is where it should continue to be.

Consider this classic video from 1997, which includes a well-known quote from Steve Jobs:

Most notably, Jobs states here (and in many variations elsewhere): “Start with the customer experience and work backwards.” In the advice context, we aren’t building technology, but we shouldn’t be giving our definitive advice document (regardless of its name) to compliance staff first. That should be last.

Going for the trifecta

We should start with the client experience. Some questions we can ask ourselves in each section or indeed paragraph:

- Does this improve the client experience? Do clients value this?

- Is this something the client wants to know about?

- Do we think it’s important for the client to understand this?

- Is this the best document to include this in?

- Does its inclusion improve risk management?

- Does its inclusion realistically reduce misunderstanding as a source of complaint risk?

- What kind of risks does it reduce?

- Does the benefit outweigh the cost to clarity, conciseness, and effectiveness?

- Is the time taken to produce worthwhile? Can we do so efficiently?

- Can we reduce the time taken to produce?

- What items would we like to include but aren’t worthwhile if it’s costly to do so?

- Will the production be worthwhile?

Think minutes, not pages

Everyone complains about an ‘X page SoA’, however that’s not really the issue.

The issue is:

- An SoA that is boring, hard to understand, daunting, and hard to shortcut

- An SoA that is too long

This gets worse and worse as time goes on as organisations and risk managers suffer from complexity creep, without ongoing vigilance to keep the document simple.

Ultimately, if we work on the presumption that we want a client to actually read as much of an SoA as possible, the focus shouldn’t be on page counts. The focus should be on attention span. Web designers have known this for a long time. It’s not about the words, or the pictures, or the load time, or the design, it’s all of them. Ultimately, it’s all about attention span.

You can only hold a client’s attention span for so long. A rare few (*cough* retired teachers *cough*) may read any document provided from start to finish, but attention is getting harder to maintain all the time. Attention span is a limited resource, and if you blow it you’ll have them reading the first few pages of your boring document, skimming the next few, and outright skipping the rest. That’s not in anyone’s interests.

Think as the wise men think, but talk like the simple people do. -Aristotle

If a client has a 30-minute attention span to read your document, that means:

- They can read 100% of a document that takes 30 minutes to read.

- They can read 50% of a document that takes 60 minutes to read.

- They can read 25% of a document that takes two hours to read.

Sure, this is an oversimplification. If a document takes 35 minutes to read it might be read in full because motivation kicks in to finish it, and if a document looks like it’ll take two hours to read, you might get 10 minutes of skimming at best. If a document is too complicated to follow, you can lose the reader at any time. However, the principle is illustrated.

Unfortunately, you can influence this but ultimately you don’t get to pick where the attention is spent. As a result, it might be more telling to look at it this way in the same scenario where we have 30 minutes of attention:

- For a document that takes 30 minutes to read, 100% of the text will be read;

- For a document that takes 60 minutes to read, there is a 50% chance any given text will be read;

- For a document that takes two hours to read, there is a 25% chance any given text will be read;

In practice, that means for your top five takeaways, a shorter document is more likely to have those top five be read.

We can try to attack attention span from two angles.

Try and get more minutes

Use every tool at your disposal to get more minutes. These can include:

- Supporting processes, such as:

- Giving the client a video run-down to make the document less daunting and more easily understood;

- Stressing the importance of the document, not as an insomnia aid, but as a detailed document that covers more than you could practically discuss in a meeting; and

- Providing the document the day before a presentation appointment, giving the client a chance to identify questions prior to their opportunity to ask them.

- Modern document design, such as:

- Breaking up your document with images;

- Simple, accessible language;

- Putting less important text in a less attention-grabbing spot.

Spend your minutes judiciously

Once you’ve tried to extend a client’s attention span, you now need to decide how to spend it.

In the exercise above, we covered all the things we might want in a Statement of Advice. When we’d include all things we’d want to say to the clients in writing, there’s a risk of going too far.

You might think everything is important, but if everything is important, nothing is.

This extends further into risk management. Too often an advice document will include:

- All possible disadvantages (not just those required by Corps Act 927D);

- All possible risks, even those which are unlikely and low impact; and

- All of the above are presented with equal weight.

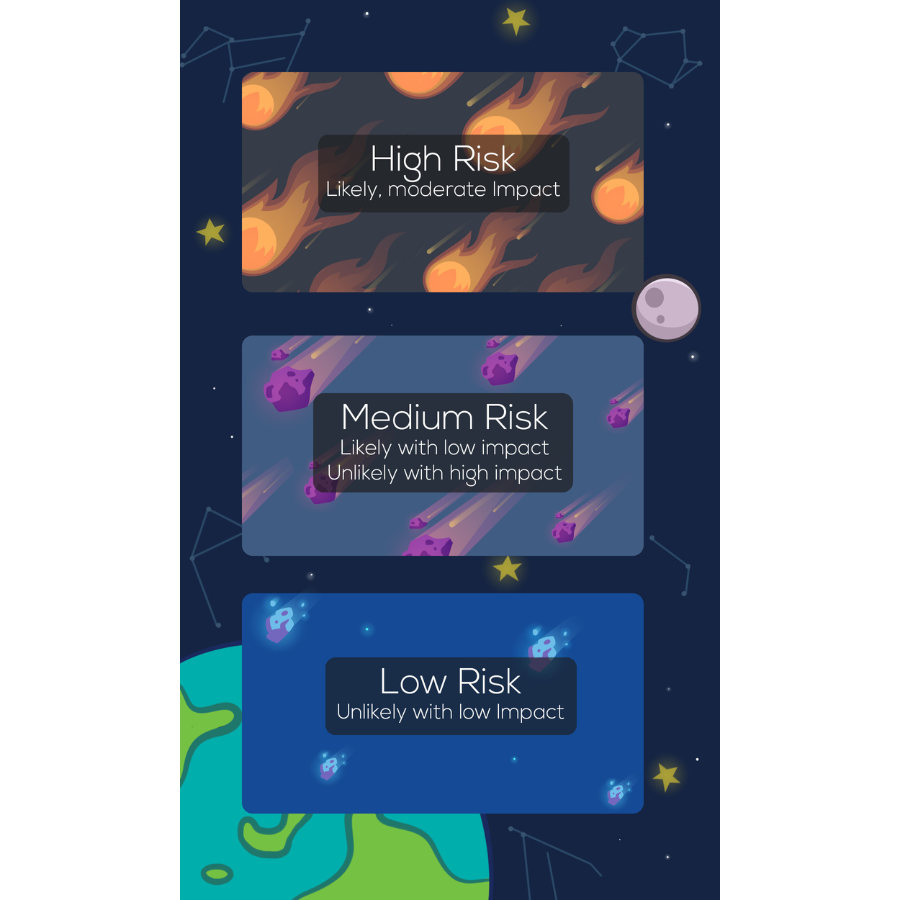

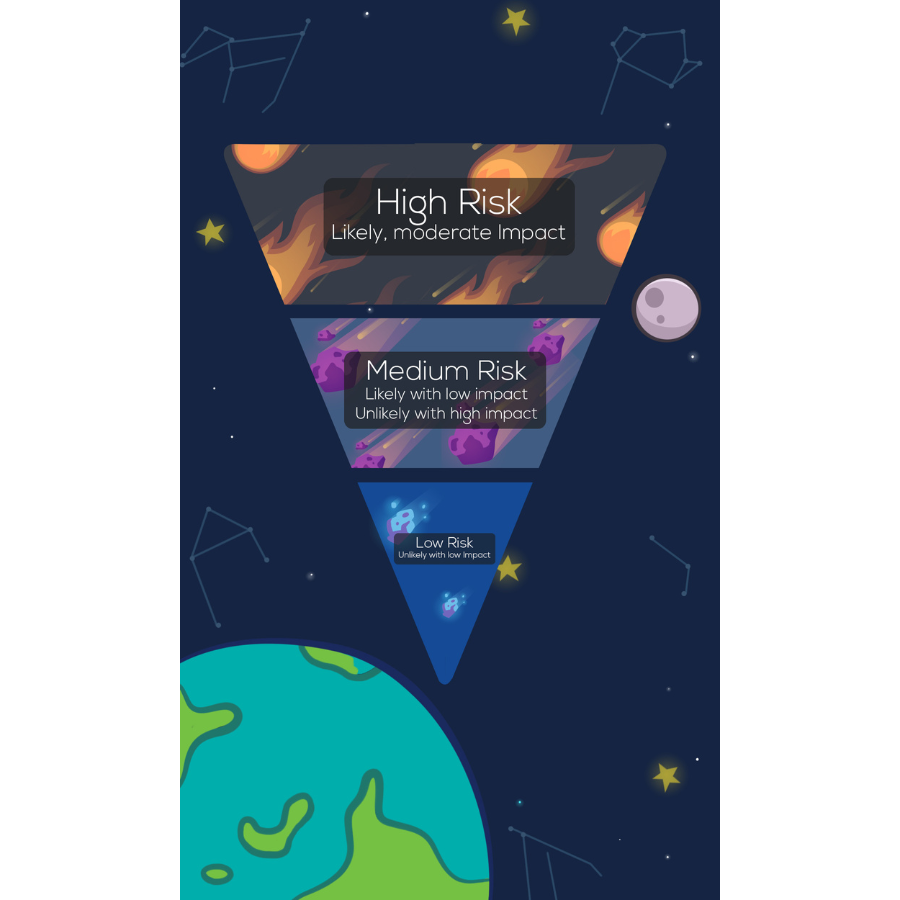

Not all risks are equal. Given we only have limited minutes of client attention, every bit of text added means that we reduce the likelihood other text will be read. Or, each unlikely and low-impact risk addressed reduces the chance a client actually reads and understands a high risk.

A more appropriate format would be to consider the genuine risk to the client, consider the weight applied to each, and even exclude smaller risks.

When considering adding a ‘low risk’ item, consider if it still adds value after considering the reduction in likelihood the client will read a ‘high risk’ item and the fact its inclusion takes us one step further from meeting our requirement to be clear, concise, and effective (Corps Act 947B(6)).

Summary

In conclusion, it’d be a mistake to think SoAs, regardless of their name, will be dead. In fact, we might actually want a master document, and we shouldn’t let a question mark over possible regulatory change prevent us from improving what we have right now.

Taking that to the next phase, if looking to redesign an advice document template, the worst place to start would be your last one. Start with what you want to include, and only cover back with what else you need to include at the end.

If this approach makes sense to you, and you wish someone could just come along and fix it for our business, you might just be interested in contacting us.

Leave a Reply